It’s hard to think of a twentieth century poet more intimately connected with a specific place than George Mackay Brown is with Orkney. The past and the present of Orkney is the unchallenged subject of his writing. Over novels, short stories and poetry, he perfected his brilliant and original vision of this place, where the rhythms of land and sea wove a pattern and harmony through his imagination.

Orkney is just a short ferry ride of the far northern tip of Scotland, but it seems a lot further. The distinctive huddle of low green islands, the high mountains, and the astonishing colours of light, immediately places us in a new world. For George, the island of Orkney was his home, his identity, and his subject. He wrote prolifically about this place, and maybe never better than in the poem Hamnavoe. Hamnavoe is the Old Norse name for Stromness, the small town where George lived and died. The poem is a celebration of that town, woven with a poignant personal memory, a memory of his father.

Hamnavoe (George Mackay Brown)

My father passed with his penny letters

Through closes opening and shutting like legends

When barbarous with gulls

Hamnavoe's morning broke

The opening lines of the poem are unmistakably George Mackay Brown, full of compact, jewel-like, brilliant images. Pamela Beasant, a poet of Orkney, calls him a “between-the-eyes” poet, his work “is so concise, so beautifully spare.” Don Paterson, another contemporary poet, calls Hamnavoe a “great place to start, because you’ll get it, and it won’t make you feel stupid. One of the reasons is that it actually trusts your intelligence.”

How did this poem make it onto the page? And how did George Mackay Brown, a largely uneducated boy from a poor family, make the journey to become a poet in the first place?

He was born in a house in Stromness that still stands; the youngest of John and Mary Brown’s five children. One of his earliest and most vivid memories of his times in the house is of being told stories by his older sister, Ruby, as they sat on a rug by the fire. He wrote his full poem at the age of eight. Unfortunately, no copies have survived of that poem, but we do know what it was about, the same subject that would continue to draw George’s gaze for the rest of his life.

[George Mackay Brown, BBC radio interview, 1989] “I remember sitting in a field, one Saturday, I think it must have been, I wrote a poem about Stromness. I took it home and showed it my mother and father and they thought it was wonderful. I think it must have been pretty awful, of course!”

“I began to write again when I was in my mid-teens. But they were very morbid sort of poems, melodramatic deaths and all that sort of thing. But I was at the age, I think, you know, where a kind of darkness comes in the mind, but only temporary, thank goodness.”

In 1940, at the age of 18, George left school with the minimum of qualifications, and even less in the way of motivation. He seemed lethargic and depressed, and ended up following his father into the postal service. Not as a postman; he sorted mail. Although he was still working away at odd poems, the chance he might have a literary career was unthinkable. John Brown had always encouraged his children to get themselves out of the rut, to make something of themselves, but at this point in his life, George seemed to have little sense of what to do with himself. It was at this time that a bleak sequence of events began to make that decision for him.

While George was sorting mail, life in the outside world was rapidly changing. When the British fleet anchored in Orkney at the start of the Second World War, these remote islands suddenly found themselves at the heart of the action. Sixty thousand soldiers poured in to protect the strategically important naval base of Scapa Flow. The population mushroomed and within a matter of months there were three servicemen in the Orkneys to every one islander.

During these war years, George’s own world was blown apart. When he was called up, his army medical revealed he couldn’t fight because he had tuberculosis. On top of this, the fear of infecting his colleagues at the sorting office meant he lost his job and he was confined to his sick bed. His family were warned that he would never be strong enough to lead a normal life. While his old classmates went off to fight, he was told he was unfit for duty. What would he do?

Someone who helped him answer this question was an army officer who was billeted in the Brown household. His name was Francis Scarfe, an established poet and university lecturer who introduced the convalescing George to a whole raft of writers, including D.H. Lawrence and Dylan Thomas, as well as the music of Mozart, Beethoven and Mendelssohn. More than this, though, he encouraged the awkward adolescent to develop his own poetic voice. For a brief period, George poured his energies into writing.

But undoubtedly the greatest impact on George’s life during the war years was his father’s death. The war effort involved the whole of the Orkney community. George’s father had the gruelling job of spending freezing cold nights tending the isolated lookout huts that lined Scapa Flow. It was while he was on duty in July 1940, that the sixty-five-year-old John Brown died suddenly of a heart attack. It must have been a dark time for George, trying to come to terms with his father’s death, and finding himself too ill to ever work. He was stuck in the rut that his father had always hoped his children would avoid. It was seven years later, by which time George was twenty-five, that he felt able to write about his father in the poem that eventually became Hamnavoe.

Hamnavoe is a vividly visual poem that evokes the life and the spirit of a small Orkney community. In it, the town unfolds for us as a postman makes his rounds through the streets. That postman is John Brown, the poet’s father. And Hamnavoe, whilst being a poem of tribute to a place, is also an elegiac hymn to John Brown, a poetic letter written by a son to his father.

In that fantastic first half of Hamnavoe, even though it’s set in a long-gone era, the townsfolk, not just John Brown the postman, but the fishermen, the merchants, seem to be hotwired into life in every line. Especially evocative is where George is describing the men drinking at the bar, where he talks about “Three blue elbows fell, regular as waves, from beards spumy with porter”, the idea of the elbows rising and falling like the waves outside.My father passed with his penny letters

Through closes opening and shutting like legends

When barbarous with gulls

Hamnavoe's morning broke

On the salt and tar steps. Herring boats,

Puffing red sails, the tillers

Of cold horizons, leaned

Down the gull-gaunt tide

And threw dark nets on sudden silver harvests.

A stallion at the sweet fountain

Dredged Water, and touched

Fire from steel-kissed cobbles.

Hard on noon four bearded merchants

Past the pipe-spitting pier-head strolled,

Holy with greed, chanting

Their slow grave jargon.

A tinker keened like a tartan gull

At cuithe-hung doors. A crofter lass

Trudged through the lavish dung

In a dream of cornstalks and milk.

In "The Arctic Whaler" three blue elbows fell,

Regular as waves, from beards spumy with porter,

Till the amber day ebbed out

To its black dregs.

The postman, John Brown, was a popular figure in Stromness, and his son too became a well-known character about town. Everyone still talks about George as a friend, and his spirit seems tangible in the place. As he said in 1976, “Everybody’s life is conditioned, to a great extent by the place that they live in. Stromness is a, well, it’s a beautiful place to live in, I think. It’s a sort of microcosm of the whole of life in quite a small area. You can see things whole and complete from any point of view. I don’t know whether there’s any other place on earth quite like it.”

The physical geography of Stromness and the Orkney isles is clearly important to the voice and the style that George developed. “Over the years, George has become the Orkney poet. He has become the person who has portrayed Orkney. Ironically, he hardly visited any of Orkney. He lived in Stromness, but apart from that, he didn’t even go into Kirkwall very often. But his knowledge of historic Orkney was considerable. He got his first book of the sagas in the local library, and he didn’t return it.” (Megan Macinnes, Orkney poet and friend of George.)

In the early 11th century, the Earldom of Orkney was shared between two cousins, Magnus and Haakon. When the two cousins feuded, they met at a peace conference at which Haakon treacherously ordered the murder of Magnus. Magnus went to his death willingly, apparently as happy as a man on his way to a feast, choosing to martyr himself for his cousin’s soul and for the peace of the Orkney Isles. His bones are immured in a pillar in the Cathedral.

The cathedral represented to George a physical link to Orkney’s past, while the sagas gave him the key to unlock the simple yet arresting narrative of his island’s heritage.

[Extract from Saint Magnus in Egilsay, by George Mackay Brown] “Bow your blank head. Offer your innocent vein. A red wave broke. The bell sang in the tower. Hands from the plough carried the broken saint under the arch below the praying sea. Knelt on the stones.”

The Orkney sagas, though, were not just influential upon George’s subject mater, but also upon his style. It was from the sagas, it seems, that the harvested so many of the crucial elements in the flavours and the tones of his own writing. “…The most important thing about George’s poetry is compression. What George learned is the value of getting rid of words and getting down to simplicity. That was because of reading the sagas. In fact, he says in a letter to my dad: ‘It is going to be clean and crisp, and I am going to get rid of anything that is not needed.’ That is when his poetry took off.” [Megan Macinnes]

It’s absolutely this crispness and clarity, this pared-down style that makes Hamnavoe so impressive.

The boats drove furrows homeward, like ploughmen

In blizzards of gulls. Gaelic fisher girls

Flashed knife and dirge

Over drifts of herring,

And boys with penny wands lured gleams

From the tangled veins of the flood. Houses went blind

Up one steep close, for a

Grief by the shrouded nets.

The kirk, in a gale of psalms, went heaving through

A tumult of roofs, freighted for heaven. And lovers

Unblessed by steeples, lay under

The buttered bannock of the moon.

He quenched his lantern, leaving the last door.

Because of his gay poverty that kept

My seapink innocence

From the worm and black wind;

And because, under equality's sun,

All things wear now to a common soiling,

In the fire of images

Gladly I put my hand

To save that day for him.

The award-winning poet Don Paterson is an admirer of this poem, and a fan of George Mackay Brown and his lean style. “It reminds you of that open treeless, windswept landscape somehow, these standing stones and stuff. Maybe that’s just a romantic projection. But it’s hard not to hear the wind whistling through the words somehow when you read George.”

RACKWICK (a poem for Ian Macinnes, by George Mackay Brown)

Let no tongue idly whisper here

Between those strong red cliffs,

Under that great mild sky

Lies Orkney's last enchantment,

The hidden valley of light

Sweetness from the clouds pouring

Songs from the surging sea

Fenceless fields,

Fishermen with ploughs and old heroes

Endlessly sleeping

in Rackwick's compassionate hills.

But to George, Rackwick also seemed to be a melancholy place. The derelict croft houses, the slow fires of rust devouring the ploughs, and all the remnants of Rackwick’s once populous past were start evidence for him of how the rigours of the progress could leave a community to die. “He had a very idealised picture of communities in one sense. When he went to Rackwick, what he discovered was a dying community that he wanted to memorialise. In a poem to my father, he called it Orkney’s last enchantment. He saw it as the last gasp of fishermen, crofters, working together, in a simple kind of way, without the mechanism of capitalism and all that.” [Megan Macinnes]

George’s expeditions to Rackwick presented him with a new perspective on his own community back in Stromness, and a sense of the role he could play in preserving its past. As he wrote, “I see my task as the poet and storyteller to resuce the century’s treasure before it is too late. It is as though the past is a great ship that has gone ashore, and archivist and writer must gather as much of the rich squandered cargo as they can.”

George’s expeditions to Rackwick presented him with a new perspective on his own community back in Stromness, and a sense of the role he could play in preserving its past. As he wrote, “I see my task as the poet and storyteller to resuce the century’s treasure before it is too late. It is as though the past is a great ship that has gone ashore, and archivist and writer must gather as much of the rich squandered cargo as they can.”

Throughout the 1940s, he began to find his voice as a poet, and in 1947, he wrote his first draft of Hamnavoe. But George was both personally and artistically a late developer. Although he was always writing something, it is fair to say he spent much of his 20s staring into the bottom of a beer glass. His poetry may never have left Orkney had it not been a fortuitous meeting in the summer of 1950, by which time George was nearly 30. In the Stromness Hotel, in its bar, George got to meet one of his great heroes of poetry, the wonderful Scottish poet, who was also an Orkney man, Edwin Muir, who encouraged George to come to the college where he was warden, a college called Newbattle, just outside of Edinburgh. George eagerly took up the invitation, and his time in Newbattle was vital in helping mature as a poet by introducing him to a world beyond Orkney. And, really, this marks not just the beginning of a new chapter in George’s life, but also the most important chapter in his writing life, in that those years he spent in that college would inform and influence his poetry for the rest of his life.

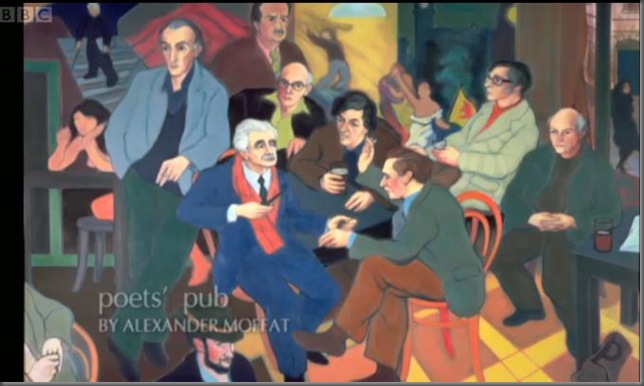

From Newbattle, George went on to Edinburgh University. In the pubs of Rose Street, he met some of the leading literary figures of Scottish poetry at that time, and grew to be respected as a contemporary.

But George was always an island man, and soon returned home to Orkney. The friends he’d made on the mainland, though, were still looking out for him. “In fact, it was Edwin Muir who smoothed the path for me,” he said, “I would never have dared to send a bunch of poems to any publisher. I got a letter from the Hogarth Press, which was a marvellous surprise for me, because I didn’t even know they had been submitted!” And by 1959, at the age of 38, George’s literary career was finally under way, spearheaded by Hamnavoe and the other remarkable poems published in Loaves and Fishes. George went on to become one of the most prolifically-published poets. Twenty-three books of poetry, six novels, as well as journalism, short stories and plays. He received a host of awards and honours for his unique writing, and was even nominated for the Booker Prize for Beside the Ocean of Time. His work was perhaps less widely read than it might have been, though, owing to George’s reclusive nature. He only ever made two journeys out of Scotland in his lifetime.

It is hard to quantify George Mackay Brown’s influence on the poetry that has been written since, in Scotland and in Britain. Don Paterson says, “I just think it sometimes takes the quieter voices a long time to be heard clearly. It’s really only in the last… maybe 15, 20 years that we’ve really started to hear his influence come through, maybe largely by poets of my generation. George has become a touchstone point in terms of how you deal with the image, how you talk about nature in a way that doesn’t seem to appropriate it, and how you tune your ear. He has become a real touchstone point.”

It is hard to quantify George Mackay Brown’s influence on the poetry that has been written since, in Scotland and in Britain. Don Paterson says, “I just think it sometimes takes the quieter voices a long time to be heard clearly. It’s really only in the last… maybe 15, 20 years that we’ve really started to hear his influence come through, maybe largely by poets of my generation. George has become a touchstone point in terms of how you deal with the image, how you talk about nature in a way that doesn’t seem to appropriate it, and how you tune your ear. He has become a real touchstone point.”

“A lot of people write about St Kilda, which is the outermost of the Outer Hebrides, but no-one much writes about Luing, which is one of the Inner Hebrides, because it’s so easy to get to. But it’s an even stranger place…” [Don Paterson]

Pamela Beasant was a friend of George’s during the last years of his life. “Nobody will ever write about Stromness or maybe even think about Stromness in the way he did. It’s odd, but when he died, it was like a physical absence, there was a hole in the town, it was very noticeable. Even now it’s still noticeable when you walk past his house and look up. He often had daffodils at the window. And his absence is almost palpable, and I found that, for quite a long time after he died, somehow or other, Stromness had shed a skin in some way, and was just Stromness again.”Luing (Don Paterson)

When the day comes,

as the day surely must,

When it is asked of you

and you refuse

to take that lover's wound again,

that cup

of emptiness

that is our one completion,

I'd say go here

maybe

to our unsung

innermost isle: Kilda's antithesis,

yet still with its own tiny stubborn anthem,

its yellow milkwort and its stunted kye.

Leaving the motherland

by a two car raft,

the littlest of the fleet,

you cross the minch

to find yourself, if anything,

now deeper in her arms than ever,

sharing her breath.

Watching the red vans sliding silently

between her hills.

In such intimate exile,

who'd believe the burn behind the house

the straitened ocean written on the map?

Here,

beside the fordable Atlantic

reborn into a secret candidacy,

the fontanelles

reopen

one by one

in the palms,

then the breastbone

and the brow,

Aching

at the shearwater's wail,

the rowan

that falls beyond all seasons.

One morning

you hover on the threshold,

knowing for certain

the first touch

of the light

will finish you.

“For schoolchildren, it’s now the poem they always have to do. It becomes the one, ‘Oh, no, another George poem, good grief!’ But in the long term it’s given Stromness a kind of history that it didn’t ever think it would have. Stromness never expected to be a place where people from all over the world were coming to see the kind of imagery George was talking about. What George did for the community was make it feel more aware of the specialness of things.” [Megan Macinnes]

After a few days here, one realises what a great poetic guidebook Hamnavoe is to this town. It conjures up the history the land, the skies, the people, and in a very subtle way, it conjures up George, too. The best image in the whole poem, though, comes right at the end.

In writing this poem, George is saving that day for his father, but he’s also trying to save that day for himself, by capturing the spirit of this town, through which John Brown walked every day on his rounds. Most importantly, this is why the poem has such power. In those last lines, George Mackay Brown is voicing a shared wish of every grown-up child towards every parent, to freeze-frame them in the landscape in which they are most alive to us, wherever that may be.In the fire of images

Gladly I put my hand

To save that day for him.

Written and Narrated by Owen Sheers: The Poet’s Guide to Britain, BBC Four.

1 comments:

Oh dear. Now I'm going to have to collect all of this wonderful poet's work! I fear for my bank balance.

Post a Comment